O-expressions

I have been working on a particular kind of syntax that I call o-expressions. They are nearly as regular as s-expressions while looking much more similar to popular languages. The source is here.

- All tokens are split into two categories: "operator" and "not an operator". This depends only on the token and not on context.

- All tokens have the same syntactic properties regardless of where they are located.

- Juxtaposition is a left associative operator that means

apply(works like in Haskell, basically). - It is an operator precedence syntax. All you need to parse it is a

precedence table.

- The operator precedence graph is static and cannot be customized: custom operators are allowed, but they all behave the same.

Now, the idea is this: by picking the set of special operators carefully enough, you can create syntax which is almost as generic as s-expressions, while requiring significantly less parentheses and containing a lot more visual hints.

As general guidelines, the priority graph should be:

- Simple: there shouldn't be so many operators that it's impossible to memorize all of them.

- Parsimonious: if it's not intuitively clear what the mutual priority of two operators should be, then it should be a syntax error to mix them.

- Ubiquitous: every code base of a reasonable size should be expected to contain all the operators in the graph at least once.

These guidelines do not forbid custom operators. What they do say is that all custom operators should behave the same, that you shouldn't mix them together (because it's not clear what that means), and that the sine qua non condition to place an operator outside the "Other" category is that it should be so common that you can't ignore its existence.

Adapting to s-expressions

Liso is an implementation of O-expressions (written in Racket) that compiles to s-expressions.

It looks like that:

@varsrec

odd?[n] =

@if n == 0:

#f

even?[n - 1]

even?[n] =

@if n == 0:

#t

odd?[n - 1]:

even?[30]

(varsrec

(begin (= (odd? n)

(if (== n 0)

#f

(even? (- n 1))))

(= (even? n)

(if (== n 0)

#t

(odd? (- n 1)))))

(even? 30))Liso on the left, equivalent s-expression on the right (top and bottom if you are on mobile).

Translation rules

| Rule | O-expression | S-expression |

|---|---|---|

| Operator | x <operator> y | (<operator> x y) |

x <op> y <op> z | (<op> x y z) | |

x <op1> y <op2> z | (<op1>_<op2> x y z) (op1 != op2) | |

x `op` y | (op x y) | |

| Apply | x y | (apply x y) |

x y z | (apply (apply x y) z) | |

| List | [] | (list) |

[x] | (list x) | |

[x, ...] | (list x ...) | |

| Apply+List | x[y, ...] | (x y ...) |

| Group | {} | (begin) |

{x} | x | |

{x, y, ...} | (begin x y ...) | |

| Arrow | x => y | (x y) |

| Control | @K : x | (K x) |

@K x : y | (K x y) | |

@K x, y : {z, w} | (K (begin x y) z w) | |

| Sexp | (...) | (...) |

In addition to these, the indent and line break rules are:

- Indent: Every single indented block is equivalent to wrapping it

in

{}s. That is to say,INDENT == {andDEDENT == }. - Line break: There is an implicit comma after every single

line. That is to say,

NEWLINE == ,

That's it. Note the following:

- S-expressions are still valid: round parentheses enter and exit

s-expression processing mode. Inside s-expressions, you can use

{...}to switch back to infix syntax ([...]won't work). - At least one kind of expression,

(apply f args), is made significantly shorter, since it can now be writtenf argsorf{args}. - The Apply+List rule is partly redundant: without that rule,

x[y]would reduce to(apply x (list y))which you will note is semantically equivalent to(x y)most of the time. It is not syntactically equivalent, however, hence the need for a rule. - The role of priority disambiguation is given to curly braces. Thus

the s-expression

(* (+ a b) c)would have to be written{a + b} * c.

The rule Arrow is a convenience rule that builds a pairing of the

form (x y). Such pairings are ubiquitous in let forms, but also in

cond, case, match, etc. The rule saves us from redefining most of

these control structures.

Definition of operator

One very simple rule: if a token starts and ends with an operator character, it is an operator. Otherwise, it is an identifier (or a literal):

- Literal:

1 1.4 4/3 "string" 'character' - Identifiers:

x abc z123 call/cc let* 1+ ^xyz - Operators

- Infix:

+ - **% ^xyz^ /potato/ <yay> *a/b&c% NEWLINE - Prefix:

. ^ ( [ { INDENT @keyword - Suffix:

) ] } DEDENT

- Infix:

There are a few special cases: . and ^ correspond to quasiquote

and unquote, so they are prefix, and I will explain @keyword

later.

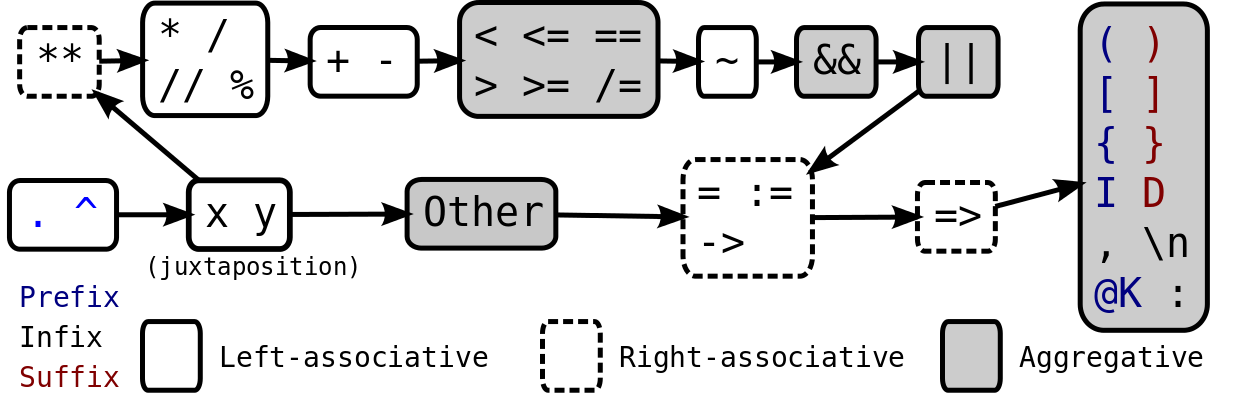

Priority graph

(I and D mean indent and dedent respectively, i.e. the start and end

of an indented block)

If you can follow the arrows from an operator to another, it means the first has priority over the second. If there is no path from either to the other, then they can't be mixed. For instance:

a b c d ==> (juxt (juxt (juxt a b) c) d)

a + b * c ==> (+ a (* b c))

a b + c ==> (+ (juxt a b) c)

a +++ b = c ==> (= (+++ a b) c)

a +++ b + c ==> error

"Aggregative" operators are merged into a single expression:

a && b && c ==> ((&& &&) a b c)

a > b >= c == d ==> ((> >= ==) a b c d)

a `b` c `d` e ==> ((b d) a c e)

@while x: y ==> ((while :) x y)

Control structures

The rule Control caters to the following general use case: "you have

a control structure, the first argument is special, sets things up,

etc. and then you have a body or some arbitrary number of

clauses". Virtually all common control structures in Racket fall in

that category: let, lambda, when, for, match, define,

etc. Others, like cond, case, require, provide have no special

argument, but that's even easier to deal with.

Long story short, if we can devise a nice syntax that takes care of this in general, we're not really going to need anything else. Furthermore, the syntax can serve as a formatting hint to editors, sparing us the trouble of configuring the layout of special macros.

I'm still not entirely sure what syntax to use here, but just now I've converged to this one:

@name foo, bar, ...:

humpty

dumpty

...

(name (begin foo bar) humpty dumpty)It looks fairly good in general:

@define pr[x]:

display[x]

newline[]

@when x > 0:

pr["positive"]

@let x = 1, y = 2: x + y

@let* x = 1

y = x:

x + y

@match [1, 2, 3]:

[a] => 1

[a, b] => 2

[a, b, c] => 3

[a, b, c, d] => 4

@provide:

myfunc

@except-out all-from-out[racket]:

let, let*, letrec, lambda

@rename-out:

mylet => let

mylet* => let*

myletrec => letrec

mylambda => lambda

I've considered a few other options. Keep in mind, though, that I am

aiming for a general syntax: when is not a keyword. This limits

options.

Another limitation is that the syntactic role of a token cannot vary

from a context to another. For instance, in Python, the relative

priority of the comma and the = operator varies: a, b = c

(assignment to tuple) versus f(a, b = c) (function arguments). Its

priority relative to in also changes depending on whether we're in

list comprehension context or not. These variations are not acceptable

here.

Variant

Alternatively control structures could be made to look like this:

define pr[x]:

display[x]

newline[]

when {x > 0}:

pr["positive"]

let {x = 1, y = 2}: x + y

provide:

myfunc

(That was actually my original solution)

The downside is that any expression involving operators needs to be

wrapped in brackets. It may also be a bit easier to mess up, since

with @name ... :, omitting one of the parts is equivalent to a

bracket mismatch.

Changes from Scheme

There are some problems with the translation a few existing control

structures. Let's take lambda for instance. In a nutshell, there are

two ways to write it in Liso:

;; Using the syntax for (x y z)

@lambda x[y, z]:

...

;; Using s-expressions directly

@lambda (x y z):

...

;; Original

(lambda (x y z)

...)The first way is a bit odd, because x stands out from the other

arguments. The second way falls back to s-expressions, which we'd

rather not do. We'd prefer to have something like this:

@lambda x, y, z:

...

;; or this

@lambda [x, y, z]:

...

Now, we could easily redefine lambda to work like that. The only

issue is that it won't be the original lambda any more.

At the core of the problem is the fact that the first element of an

s-expression can be special (a function, a keyword, etc.) or not

special (just the first element of some list). However, languages

based on s-expressions offer absolutely no syntactic clue as to which

one may be the case. That's why you can have code like

(lambda (f g) (f g)), where the same subexpression (f g) is found

twice, but with starkly different semantics each time.

O-expressions, on the other hand, correspond to s-expressions where

the first element is always special: it's a function, or an operator,

or some keyword like begin or list. All things considered, I would

say that it is a saner policy than s-expressions, but when translating

to the latter, it causes some friction.

I redefined a few existing macros under new names. I also took the opportunity to alias a few others to operators.

| Liso | Scheme |

|---|---|

@vars a = 1, b = 2: ... | (let ((a 1) (b 2)) ...) |

@vars* a = 1, b = 2: ... | (let* ((a 1) (b 2)) ...) |

@varsrec a = 1, b = 2: ... | (letrec ((a 1) (b 2)) ...) |

[x, y, z] -> ... | (lambda (x y z) ...) |

f[x] = ... | (define (f x) ...) |

x := v | (set! x v) |

x :: xs | (cons x xs) |

x ++ y | (string-append x y) |

x ** y | (expt x y) |

x || y | (or x y) |

x && y | (and x y) |

! x | (not x) |

Examples

Each example shows side by side the Liso code and the Scheme code that it is directly translated to. This is sometimes slightly unfair, since the translation can be longer than idiomatic Scheme code would otherwise be. You can judge for yourself.

First we have the canonically terrible recursive implementation of fibonacci numbers:

fib[n] =

@if n <= 1:

n

fib[n - 1] + fib[n - 2]

fib[30]

(= (fib n)

(if (<= n 1)

n

(+ (fib (- n 1))

(fib (- n 2)))))

(fib 30)In the second example I implement a function that filters all the

elements of a list that match some predicate. Then I get the minimum

positive element of a list by exploiting the fact that juxtaposition

is apply. The match construct used here is the one that comes

standard with Racket. It is unmodified.

filt[?, xs] =

@match xs:

[] => []

[x, rest, ...] =>

tail = filt[?, rest]

@if ? x:

x :: tail

tail

results = filt[[x] -> x > 0

[0, 1, -2, -3, 4]]

min results

(= (filt ? xs)

(match xs

((list) (list))

((list x rest ...)

(begin

(= tail (filt ? rest))

(if (? x)

(:: x tail)

tail)))))

(= results

(filt (-> (list x) (> x 0))

(list 0 1 -2 -3 4)))

(apply min results)Now for something a bit more interesting, I define a new operator. There is no need to give it a priority or associativity, because all priorities are set in stone at the beginning.

>>> x =

display[x]

newline[]

>>> "hello!"

(= (>>> x)

(begin

(display x)

(newline)))

(>>> "hello!")Exploiting operator aggregation:

culprit <in> room <with> weapon =

format[msg, culprit, room, weapon] $

msg = "Mr. Boddy was killed by ~a in the ~a with the ~a"

"Colonel Mustard" <in> "ball room" <with> "candlestick"

(= (<in>_<with> culprit room weapon)

($ (format msg culprit room weapon)

(= msg "Mr. Boddy was killed by ~a in the ~a with the ~a")))

(<in>_<with> "Colonel Mustard" "ball room" "candlestick"))

Cool, isn't it? But the coolest part of Scheme is the macros, so let's

see how well we fare there. What follows is a definition of a swap

operator. It uses Racket's define-syntax-rule unchanged.

@define-syntax-rule x <=> y:

@vars temp = x:

x := y

y := temp

@vars a = 1, b = 2:

a <=> b

(define-syntax-rule (<=> x y)

(vars (= temp x)

(:= x y)

(:= y temp)))

(vars (begin (= a 1) (= b 2))

(<=> a b))Now for a more complex example, a for control structure that loops

through ranges.

@define-syntax for:

@syntax-rules [list, begin]:

for[{}, body, ...] =>

{body, ...}

for[{spec, rest, ...}, body, ...] =>

for[spec, for[{rest, ...}, body, ...]]

for[var = start <to> end <by> increment, body, ...] =>

@vars loop[var = start]:

@when var <= end:

body

...

loop[var + increment]

for[var = start <to> end, body, ...] =>

for[var = start <to> end <by> 1, body, ...]

@for x = 1 <to> 3

y = 10 <to> 30 <by> 10:

display[[x, y]]

(define-syntax for

(syntax-rules (list list begin)

((for (begin) body ...)

(begin body ...))

((for (begin spec rest ...) body ...)

(for spec (for (begin rest ...) body ...)))

((for (= var (<to>_<by> start end increment)) body ...)

(vars (loop (= var start))

(when (<= var end)

body

...

(loop (+ var increment))))))

((for (= var (<to> start end)) body ...)

(for (= var (<to>_<by> start end 1)) body ...))))

(for (begin (= x (<to> 1 3))

(= y (<to>_<by> 10 30 10)))

(display (list x y)))

Advantages

Versus Java and its ilk

Unlike Algol-type syntax, it adequately mirrors the strong points ofs-expressions:

- The syntax is very general and can be adapted to a very wide variety of semantics.

- It is regular: every token has the same syntactic properties regardless of where it is located.

- It is homoiconic: from any expression, it is straightforward to figure out what the resulting AST is.

- Writing macros and new constructs is easy: it requires neither parsing knowledge nor even pattern matching (though the latter is always nice to have).

- New constructs integrate themselves seamlessly into the language.

Versus s-expressions

Unlike s-expressions, it adequately mirrors the strong points ofAlgol-type syntax:

- Visually, it is very similar to widely popular languages such as Python. This makes it more accessible.

- There are less incentives to collapse nesting, because a wisely picked set of core operators can encode the necessary structure without "looking bad".

There is also an opportunity to "fit" extra semantics into apply.

see here for instance.

Other features

Liso also mirrors a few strong points of Haskell's syntax:

- There is no need to provide an

applyfunction, because juxtaposition isapply. O-expressions naturally lend themselves to currying, though this might or might not be apparent depending on whether functions curry their arguments or take a tuple of them. - The syntax is more "referentially transparent" than most, since

expressions in the vein of

x = [1, 2], f xwill generally work. That isn't true in C, Java or Python. - It is possible to define arbitrary operators and to use functions as operators. In order to aid readability, however, their priority cannot be customized.

Concluding remarks

In my opinion, the syntax I've cooked up is a competent alternative to s-expressions. I also prefer it to sweet expressions, which is the best attempt at an alternative syntax for Scheme that I've seen so far.

It is a more complex syntax than Scheme, but for me it hits a sweet

spot. It enforces a syntactic distinction between function/macro calls

(where car is special) and lists of things (where car is not

special), but in practice languages based on s-expressions tend to

erase it. This makes the translation occasionally awkward, though I

think it is more a problem with s-expressions: it makes sense to

distinguish lists of things from actual calls syntactically.

I plan on porting the syntax to JavaScript and Python, which would give both languages macros and the upsides of s-expressions without the downsides.

The source code is available here. The repository contains more examples and some instructions on how to try it. At the time of this writing, the Planet version of Liso (1.1) is out of date, I'll update when I make up my mind on a few things.